We booked this historical excursion well before Christmas not realizing that this day would be the first of a severe cold front sweeping across Shanghai. It has been relatively mild all winter so it was something of a shock to be out for a 2+ hour walk in -6 with a wind chill that felt like ice was slicing through your flesh!! We all wore masks the entire time not because of social distancing or COVID but because we were bloody cold!!!

The trip started at this exciting point

The creek feeds into the Huangpo River and was once an area filled with industrial and commercial activity. Some of the old warehouses remain and have been repurposed into shops, galleries and offices. The architecture was an attractive mixture of brick and wood and so different from the rest of the high rises which litter modern Shanghai.

This shop sold fine bone China and we learned that this did not originate in China but in the UK. Bone ash of animals who eat vegetables like cows and sheep are added to the clay which gives strength & resilience to the delicate shapes.

The whole area was under the control of a gangster mafia-style man called ‘Big Ears’ Du Yuesheng, who in the 1930s rose from being a farmer’s son to running protection rackets, the drug scene and all prostitution in Shanghai. He was able to do this by influencing the police and political leaders of the time. He was so powerful that even Chiang Kai-Shek had to co-operate with him. Big ears was even appointed chair of the board of opium suppression – which was the equivalent of giving a grizzly bear the keys to a honey factory!

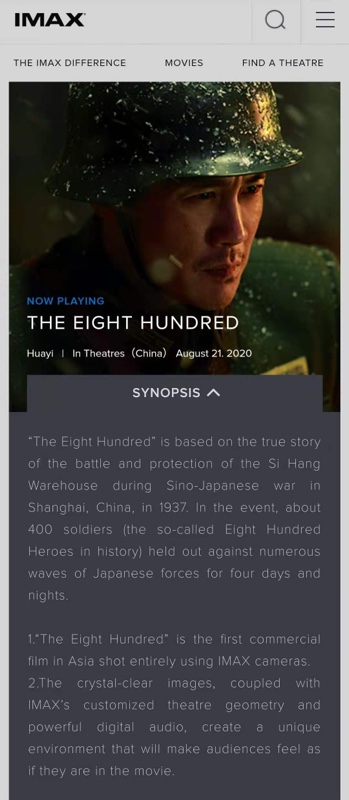

In 1937 West Suzhou Creek was the site of a major battle in Shanghai between a small group of Nationalist soldiers who were bravely holding out against the invading Japanese army. This is a piece of history that is not really well known in the west.

China in the 1920s was a largely agrarian society with little education and a poorly equipped army. Shanghai was the exception and had developed to be a hub for international business and finance, based in a large part on the opium trade. Shanghai was divided up by the European powers into ‘concessions’ and here the bright young things danced and partied living a life of decadence in stark contrast to the poverty in the Chinese parts of the city.

Japan, on the other hand was an aggressive industrialized nation with supremacist tendencies similar to those of Nazi Germany. They had a well organized and disciplined army made up of literate professionals and not the rough farmers of the Chinese military. Japan had invaded northern China and occupied Beijing, then brashly claimed that they could overrun Shanghai in 3 hours.

At this time the European nations did not want to engage Japan in a conflict. So they had a tacit agreement that the various concessions in the city would be untouched. This largely happened, but to achieve that the Japanese were unable to deploy their aerial bombers which would have destroyed great swathes of Shanghai including the concessions and the Chinese army took strategic advantage of this.

One group of soldiers was sent in from the countryside in the belief that they were going to rescue the wounded but instead were deployed to guard a warehouse on the opposite side of the creek to the British Concession. The warehouse was a reinforced storage facility for 4 banks which was virtually impregnable. There were only 400 of these Nationalist soldiers but they stated that there were 800 in an effort to try to deter the Japanese.

While the bright young things and international observers stood and watched from the opposite side of the creek these two sides fought it out and over the course of 3 days the Chinese soldiers held on to their position against all odds. The Japanese caved in to international pressure and finally agreed to give the Chinese soldiers safe passage across a bridge to the British Concession but then renegaded on the agreement and shot at the soldiers as they tried to cross the bridge. Astoundingly over 200 made it across. They are remarkable heroes but because they were all Nationalists and under the leadership of Chiang Kai-shek, the ruler deposed under Chairman Mao’s Glorious Revolution, they have been largely forgotten by Chinese history until recently.

The Si Hang warehouse still stands in Shanghai today, it’s splatter of bullet holes a stark reminder of the horror and destruction of war.

The museum inside dealt with the story in an informative and sensitive way.

This exhibit has the names of all the soldiers in the 88 Division where they are known. Records were scant so some names have been lost. Where that has happened there is a simple 88D block.

There is a new Chinese film out which commemorates the battle and I would recommend it to anyone who would like to know more about this chapter of Chinese history. It is quite graphic but a real insight into a subject that we in the west are not overly familiar with. Fortunately it is subtitled.

The sad thing is that once safely across the bridge the soldiers were taken by the British to an internment camp where they languished for over 3 years until the attack on Pearl Harbor after which the Japanese overran all the concessions and captured the soldiers. They were then sent to do hard labour for the Japanese until the end of world war 2.

We finished up walking along the creek to the site of the Bank of China branch that in its basement once housed all the treasures from inside the Forbidden City. The Nationalist party moved them there for safe keeping at the time of the Japanese invasion and then shipped them all out to Taiwan, where a large number of Chiang Kai-shek’s followers fled in the face of the communist revolution. Which explains why a tour of the Forbidden City today is just a walk around the empty buildings.

It was nice to do some learning amidst all the seasonal revelry. And to discover more about this city that we are living in.